Consumer-driven contract testing with Pact and Python

Today microservices play a very important role, as they have become the architecture of choice for many companies. The web is full of articles and talks about the amazing advantages of this architecture, e.g.:

- Faster time to market

- Smaller teams

- Ease of maintainance

- Independent scalability of components

- Independent choice of programming languages

and so forth and so on. Nothing in life is free of course, and all these amazing features have a cost. First and foremost your company will probably experience an exponential growth of microservices, and you may end up with something like this... With such a proliferation of services, how can you ensure the correct behaviour of your platform? How do you manage breaking changes between consumers and providers? There are many answers to these questions, but let's consider two of them.

Provider-Driven Contracts

A way to establish some order in the far-west of your services is to create a "contract" between a provider and its consumers. If we make a real life example, we may consider a restaurant as a service provider and hungry people as its natural consumers. The contract between the restaurant and its customers is clearly represented by, well, the menu! By reading the menu, consumers know exactly which services they can access and which are the rules regulating such services (e.g. price, suitability for vegetarians, etc.). Going back to microservices, we can build a restaurant service that exposes a "contract" (in JSON format) that other services can access in order to build and verify their interactions in terms of endpoints, payloads and responses. There are many ways to implement such a contract, e.g. through the JSON Schema specification.

Consumer-Driven Contracts

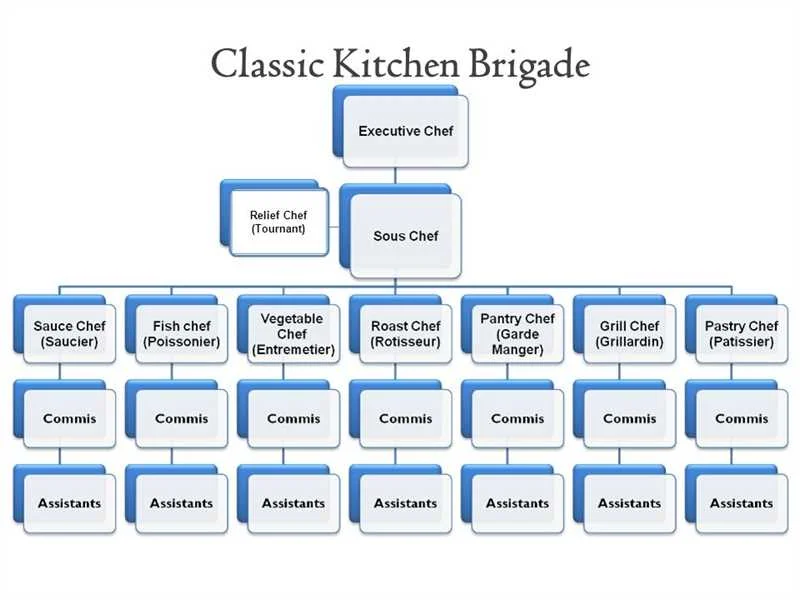

A different approach is represented by consumer-driven contracts: service consumers define the contract between them and their providers, and providers must honour such contracts. The first time I heard of this approach I thought: "Well, this is stupid!". I can't walk into a restaurant, define my own menu and expect the restaurant to provide what I want! Well, let's be a little bit more open minded and consider the following image:

A kitchen brigade can be seen as a collection of microservices that need to

cooperate in order to produce the final output. In this situation it makes a lot

of sense for one microservice, e.g. the SousChefService, to define a contract

with its providers, e.g. the RoastChefService. The correct behaviour of the

overall architecture is ensured because every service must honour contracts with

its consumers, and breaking changes are detected (and possibly avoided, or at

least discussed) as soon as they happen. How to achieve that? A possible

implementation of this pattern is represented by Pact, a framework that provides

support for consumer-driven contract testing.

Pact

Pact is based on simple JSON files that allow interoperability between

programming languages. The examples in the next sections use a Python

implementation of the Pact framework, but the base concepts are the same. Pact

tests have two phases: provider test and consumer test. Such phases are

"asynchronous" and do not require real interactions between the two systems.

In the initial phase, the consumer defines its expectations about one or more

interactions with a provider. For example, the consumer defines what payload it

will send and what the expected response is. Such expectations are verified

locally against a mock server, generating (when successful) a JSON file

(the pact). This modus operandi represents a sort of "TDD for services",

because developers can define the interaction first, and develop the

repositories/controllers based on the responses of the mock server, with no

need for real HTTP interactions. In the second phase, the provider re-plays the

interactions recorded in the Pact file and verifies that the expectations are

met. Pact files can be stored in the provider's codebase or obtained through a

Pact Broker that acts as a "middle-man" between consumers and providers. What

about an example at this point?

Establish the contract

Let's consider the scenario where the Sous Chef relies on the Grill Chef to cook the steaks that he will then garnish and send to the clients. Such a situation can be described with a test:

@service_consumer('Sous Chef')

@has_pact_with('Grill Chef')

class GrillChefTest(ServiceProviderTest):

@given('steaks are available')

@upon_receiving('a request for a steak')

@with_request({'method': 'POST', 'path': '/steaks/', 'body': {'cooking': 'medium-rare'}})

@will_respond_with({'status': 201, 'body': {'waitingTime': 10}})

def test_steak(self):

response = GrillChefRepository.steak('medium-rare')

assert response['waitingTime'] == 10

Let's break down this test to understand how it works. The first bit is the definition of the class:

@service_consumer('Sous Chef')

@has_pact_with('Grill Chef')

class GrillChefTest(ServiceProviderTest):

pass

The class itself extends ServiceProviderTest, provided by the Pact library. It

also identifies the consumer (@service_consumer('Sous Chef')) and the provider

(@has_pact_with('Grill Chef')). Each class will generate a single pact file

that contains one or more interactions. Each method in the class describes an

interaction and has a setup section, which configures the mock server and the

test itself. The setup of the interaction requires the following:

- given: the pre-condition to the test that tells the provider how to set the initial state for this interaction. For example, this may require storing some dummy data in the DB before executing the test.

- upon_receiving: a description of the interaction.

- with_request: the payload that the consumer will send to the provider. The test itself will fail if the request is different from the one declared in the setup.

- will_respond_with: the expected response from the provider.

The resulting Pact file for this interaction is the following:

{

"provider": { "name": "Grill Chef" },

"consumer": { "name": "Sous Chef" },

"interactions": [

{

"status": "PASSED",

"providerState": "steaks are available",

"description": "a request for a steak",

"request": {

"body": { "cooking": "medium-rare" },

"path": "/steaks/",

"query": "",

"method": "POST",

"headers": []

},

"response": {

"body": { "waitingTime": 10 },

"status": 201,

"headers": []

}

}

]

}

Pact tests can be used to verify all scenarios of interest, such as wrong

requests or internal error. For example, the following example covers the case

of a 4xx HTTP error code, and it will add a new entry to the interactions

section of our pact file:

@given('steaks are available')

@upon_receiving('a request for a well-done steak')

@with_request({'method': 'POST', 'path': '/steaks/', 'body': {'cooking': 'well-done'}})

@will_respond_with({'status': 422, 'body': {'reason': 'we do not serve well-done steaks'}})

def test_steak(self):

response = steak('well-done')

assert response.status_code == 422

Once we're happy with the interactions, we can send the pact file to the Pact Broker to streamline the whole process, or simply store it in the provider's codebase for verification.

Honour your contracts

We must now make sure that the provider honours his pacts with the consumers. The test looks like this:

@honours_pact_with('Sous Chef')

@pact_uri('http://localhost:9292/pacts/provider/Grill%20Chef/consumer/Sous%20Chef/latest.json')

class SousChef(ServiceConsumerTest):

@state('steaks are available')

def test_steak(self):

DB.save(Steak(cooked=False))

Pact file can be obtained either through a URL or local file, and its location

is defined with the pact_uri decorator. We then need to define a state for

each given condition that has been defined by the consumer. In the previous

section we defined two different interactions, but they're both based on the

same pre-condition: "steaks are available". States are used to prepare the

system to run the test, e.g. store some dummy data in the test DB. The provider

is now able to re-play the interactions stored in the pact file and verify that

everything goes as expected. During this phase, the pact library will actually

start the service, make the requests defined in the pact, and verify the

responses against the expectations. The provider is therefore required to define

a pact_helper.py file that is capable to start and stop the service. The

following is a simple implementation with Gunicorn:

class GrillChefPactHelper(PactHelper):

test_port = 8080

process = None

def setup(self):

cmd = 'gunicorn start:app -w 3 -b :8080 --log-level error'

self.process = subprocess.Popen(cmd, shell=True)

def tear_down(self):

self.process.kill()

Conclusions

Pact is a framework that implements the consumer-driven contract testing pattern. It can be used to verify the interactions between "internal" services, where "internal" means that you have control over the consumers and the providers (you can try to write a consumer test for Google Maps, not sure whether they will commit to honour it though!). This technique may reduce the need for costly integration tests and give you more confidence about the overall behaviour of your systems. Pact tests can be run as part of your testing pipeline and are quite fast. But, how can pact tests prevent breaking changes??? Well, they can't! But the real value added of this integration strategy is the fact that it fosters conversations and collaboration between teams. Whenever you need to introduce a breaking change as a provider, you can immediately verify which are the consumers that will be affected by the change, and initiate a process that involves both teams with the final goal of keeping your platform up, running and healthy.

Resources

- Pact: home of Pact framework

- Official Pact implementations

- Pact Test for Python: an alternative implementation of Pact in Python, compatible with Pact 1.0, demonstrated in this article

- Consumer-Driven Contracts: A Service Evolution Pattern: more about cosumer-driven contract testing by Martin Fowler